Hi Everyone! This training is focused on its applications in the embedded context.

- 1. Cryptography Definition

- 2. The Ecosystem

- 3. A Little bit of History

- 4. Symmetric Ciphers

- 5. Block \& Stream Ciphers

- 6. Block Chaining \& Message Authentication

- 7. Asymmetric Ciphers

- 8. Asymmetric Signatures

1. Cryptography Definition

- Cryptography (AKA “encryption”) is a set of techniques & computations that are applied for securing data and communication against interception and eavesdropping.

- It is the most important tool for enhancing Cyber-security and privacy, when it is applied in a correct way

- We use it daily in our phones, our web surfing, when we travel (in epassports), when we use public transportation tickets, when we pay with credit cards etc.

2. The Ecosystem

The cryptographic ecosystem:

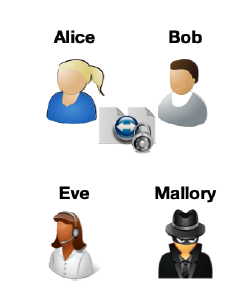

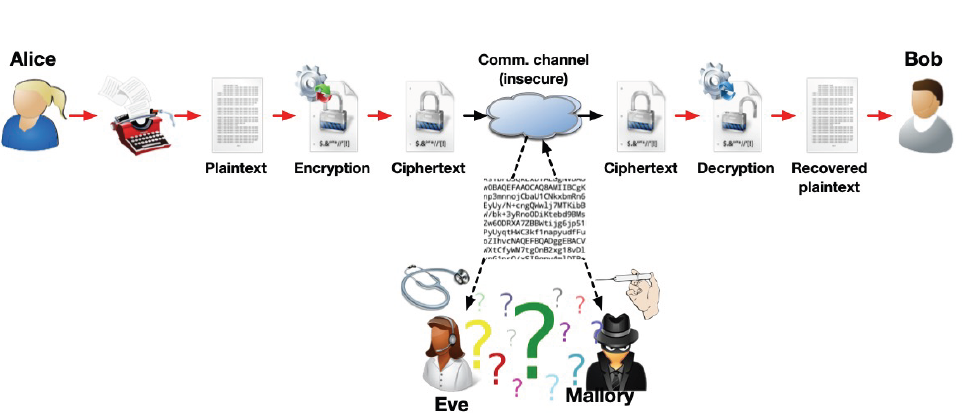

- 2 parties (A & B) that want to communicate with confidentiality, often called “Alice” & “Bob”, Sometimes we may add “Charlie”, “Dave” & others

- A passive eavesdropper, often called “Eve”

- A more active/malicious adversary, often called “Mallory”

- The message that needs confidentiality – the “plaintext”

- The encrypted message – the “ciphertext”

- The encryption/decryption process (“algorithm” or “protocol”)

Use cases - Cryptography is applied for other use cases, not only for confidentiality:

- Integrity protection:

- Examples: data in e-passports, signed software/firmware

- Identity management & establishing trust:

- Examples: TLS, proving website identities to browsers

- Access control:

- Examples: automotive RKE, diagnostics access to ECUs

- Authenticity:

- Example: cryptocurrencies (proving that transactions were committed)

3. A Little bit of History

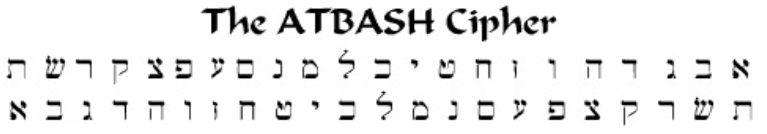

- Some words in the Bible are encrypted with a simple substitution cipher called ATBASH (from the names of Hebrew letters)

- ATBASH is based on the reverse order of Hebrew letters:

- The secret is the process and once known – it can be decrypted by anyone

3.1 Hardware-Based Cryptography

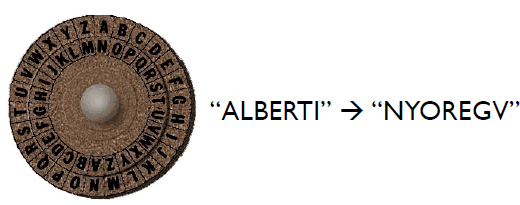

- The Middle Ages (15th century): The Alberti wheel from Italy

- The 19th century from the USA

3.2 An Important Addition –The “Key”

- A secret process like ATBASH is “Security by Obscurity” and is not really secure

- The Alberti Wheel added something new:

- Different relative positions of the inner wheel will produce different ciphertexts

- The relative position of the wheels is the “KEY” but the process stays the same: Substitute each letter in the inner wheel with the adjacent letter in the outer wheel

3.3 Terminolog

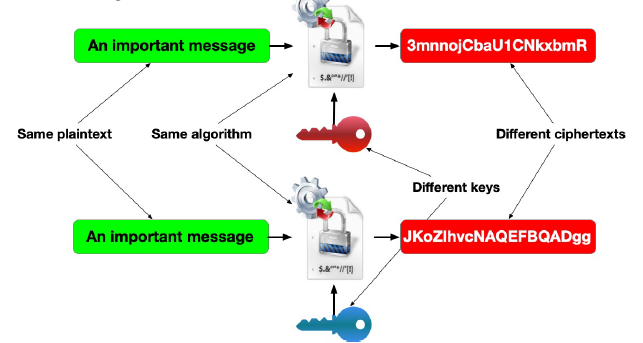

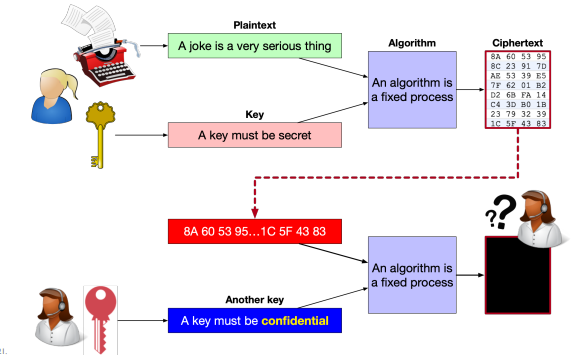

- We call the cryptographic process “Algorithm” or “Protocol”

- We differentiate between instances of the same algorithm with different keys

3.4 Kerckhoffs’ Law

- The algorithm can be public

- Only the key must be secret

- The key can be changed, transported and stored

- The algorithm may be applied to all relevant data types:

- Text, maps…

- The process should be easy (complexity ≠ security, fewer logistics = better security)

3.5 How can a cipher be decrypted?

- There is one attack method that will always succeed: Brute-force attack

- We can try every possible key until we hit something meaningful. Such exhaustive searches over the entire key space are called “brute force attacks”

- Brute force attacks will always succeed, unless we make them impractical:

- Impractical = too long = until the sun runs out of hydrogen

- Impractical = not enough silicon on earth for building HW that will do it

- Impractical = not enough silicon on earth for building HW that will do it

- Impractical = too long = for the lifespan of a device

- We want brute force attacks to be expensive enough for our adversaries

3.6 History can teach us many lessons

- We always want robust ciphers, that cannot be cryptanalyzed

- How do we know what can be trusted?

- This is not easy, better left to professional specialist mathematicians

- It is far easier to know what CANNOT be trusted, especially when the author claims that the proposed scheme is unbreakable…

- We call such bogus products “Snake Oil” and there are some telltale signs:

- 1st and foremost à not in the common standards

- Unreasonable key sizes (“128 bits is weak, we use a key with ten thousand bits”)

- Claiming “military-grade” encryption

- No peer review, “trust us, we know what we do”

- Algorithm not disclosed (remember Kerckhoff?)

- Some Cipher machine in history:

- THE ZIMMERMAN TELEGRAM –WW1, 1917

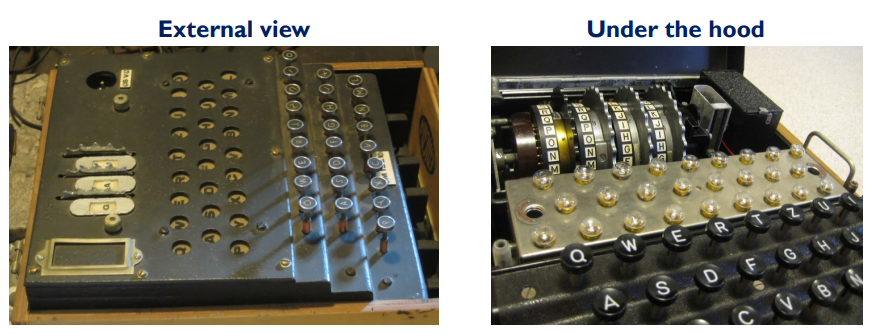

- WW2 – the German army used a sophisticated cipher machine called “Enigma”:

- Originally built for banks

- 3 rotors with ~158,000,000,000,000,000,000 combinations, a 4th rotor was added later

- Initial cryptanalysis started in Poland and results were shared with the UK, including a crude design of a cryptanalysis machine

- The German generals used a different machine with twelve rotors - the Lorenz machine

- Today cryptography happens behind the scene in many places, such as web browsers:

4. Symmetric Ciphers

4.1 A Simple Example

Example 1:

- Simple modulo addition as the algorithm:

- Encryption algorithm: Ciphertext = Plaintext + Key MOD 10

- Decryption algorithm: Plaintext = Ciphertext + Key MOD 10

- Plaintext = “9” o Key = “5” o Encryption: “9” + “5” MOD 10 = “4”

- Decryption: “4” + “5” MOD 10 = “9”

- The decryption process is identical to the encryption in this case

- The key must be pre-shared or agreed between parties

- Because both parties must apply the same key

- In the previous example, both parties applied the same key, with an identical algorithm

- In other cases, the encryption & decryption algorithms can be different but are always related

- Regardless of the algorithms, the same pre-shared key is used by both parties

4.2 The Generic Algorithm

- The algorithm is always a fixed process-

- The specific key allows multiple instances, which are opaque to each other

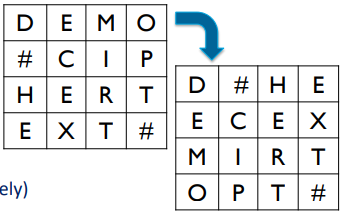

4.3 A Practical Algorithm

- Simple addition is obviously not robust enough, we want much better masking of the plaintext and much higher resistance to cryptanalysis

- The most common symmetric algorithm today is AES, which is a sequence of very simple operations, that also depend on the key:

- XOR with the key

- Write data in a 4X4 matrix

- Swap rows & columns in matrix

- Permutate values (i.e., mix bits in a column from the matrix)

- Substitute values (i.e., “C” will be mapped to “W”)

- Add/subtract modulo

- Multiple rounds (10, 12 & 14 for 128. 192 & 256 bits respectively)

- Most of the steps use simple lookup tables, so are very fast

- Other common algorithms: Triple-DES, Twofish, RC4, XTEA…

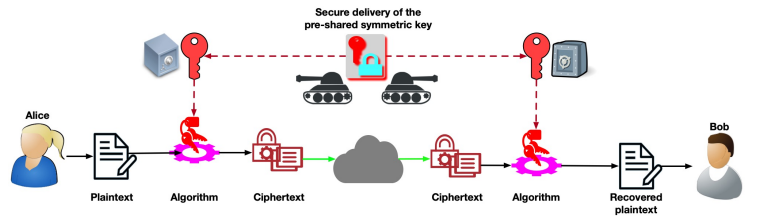

4.4 Symmetric Ciphers

- As explained earlier, Alice & Bob use the same pre-shared key for encryption & decryption

- “Same pre-shared key” = a secure process to share this key between them before they can communicate with confidentiality

- “Symmetric ciphers” can be used after both parties hold the same key

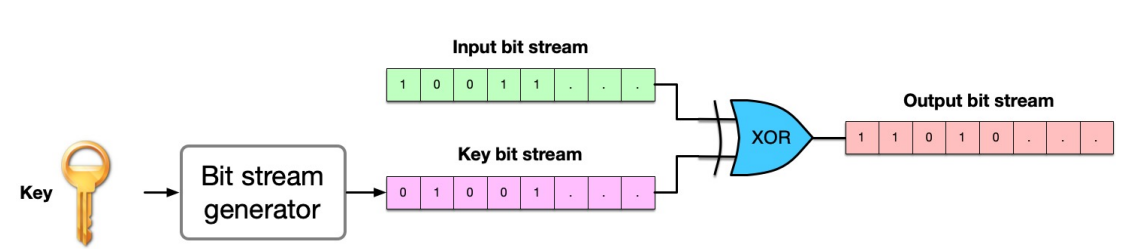

5. Block & Stream Ciphers

Two Types of Ciphers

- Ciphers should be able to handle multiple types of data (remember Kerckhoff?)

- Some types are streams of bits, other types are packets with fixed sizes

- Most ciphers operate on a fixed-size block

- AES uses a block size of 16 bytes, for the input & the output

- If the input is smaller – it will be padded to bring its size to 16

- If the input is larger – it will be split into 16-bytes blocks and each block will be processed on its own (disclaimer: this is only partially true in practice explained in the following section)

- These are called “block ciphers”

- Other ciphers treat the input data as a stream of bits

- The algorithm creates another stream of bits using the key

- The ciphertext is the bitwise-XOR of those 2 streams

- Easier to implement in hardware, useful when the input size is unknown

- These are called “stream ciphers”

6. Block Chaining & Message Authentication

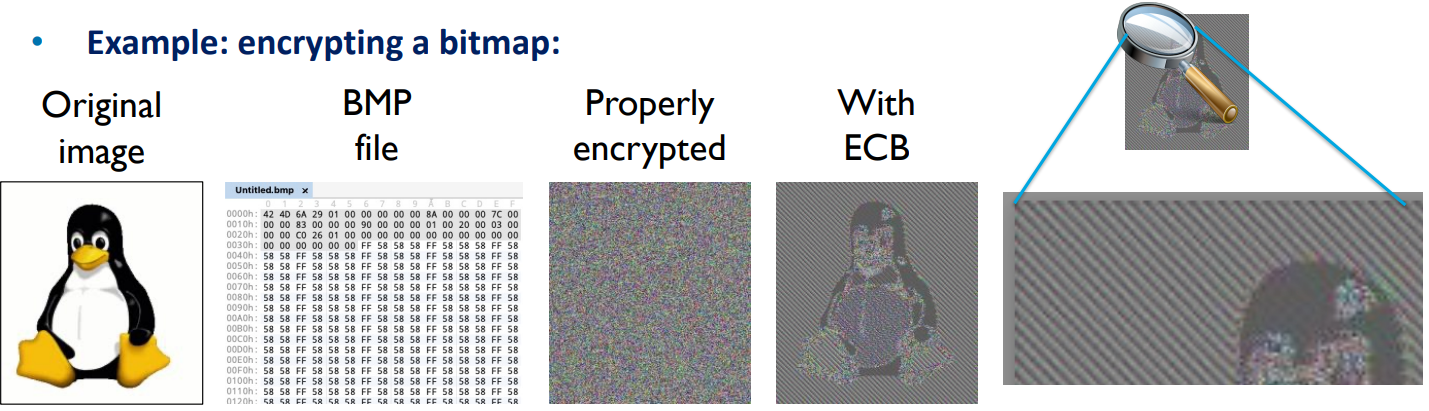

6.1 “The ‘Naïve’ Way to Encrypt

- Splitting the input into fixed-size block and processing each block on its own will still leak some information on the input!

- This happens because the same block of plaintext will always produce the same block of ciphertext

- This process is called “ECB” = Electronic Code Book

- Example: encrypting a bitmap:

6.2 ECB is Bad, We Must Do Something

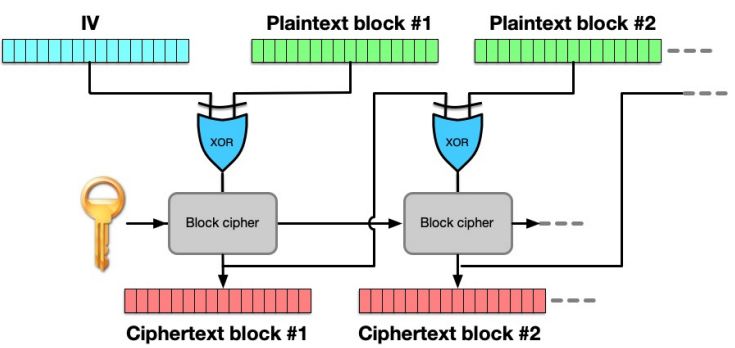

- The most common solution is mixing each block with the output of the previous block

- This is called “CBC” = Cipher Block Chaining

- The optimal way to mix bits is the XOR function

- The 1st block has no previous block, so we just add an IV (= Initialization Value) that will be XOR’ed with the 1st block

- The IV must be known to both parties and can be shared in plaintext (i.e., unencrypted)

6.3 Other Chaining Modes

- There are other chaining modes, some are focused on specific use cases such as disk encryption, others provide optimized security compared to CBC

- Some sophisticated modes are patented

- Bottom line: ECB is naïve & insecure, always pick better modes unless you need to encrypt a piece of data that is equal to or smaller than the cipher’s block size

6.4 Message Authentication

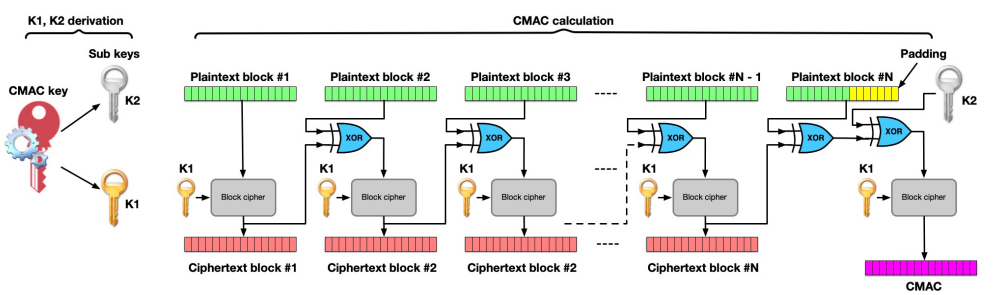

- CBC mode may also be applied for calculating MACs (= Message Authentication Codes)

- Each block depends on the previous block, and the last block depends on the entire message

- We can use the last block as a cryptographic checksum of the message à a MAC

- This is called a CMAC (= Cipher-based Message Authentication Code)

- The real-life CMAC algorithm is slightly different, and we calculate a sub-key that will be XOR’ed with the last message block if it requires padding

7. Asymmetric Ciphers

7.1 What Happens if We Have More Parties?

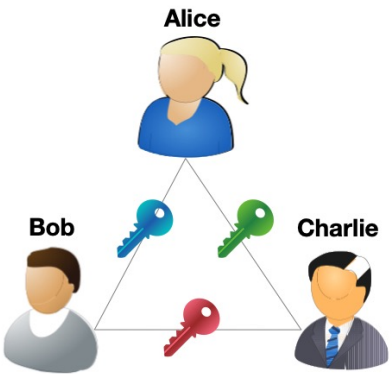

- Until now we only had Alice & Bob, with one pre-shared key

- What happens if we add Charlie?

- We need:

- one key between Alice & Bob

- another one between Alice & Charlie

- yet another one between Bob & Charlie

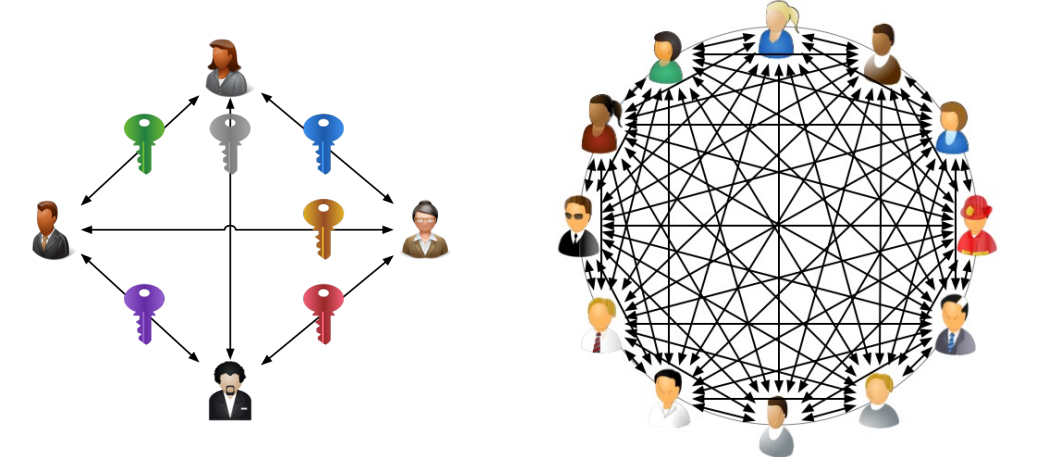

- What happens if we have much more parties?

7.2 A Scalability Problem

- We need to pre-share many different keys – a huge logistic hassle

- This is where a-symmetric cryptography enters the stage

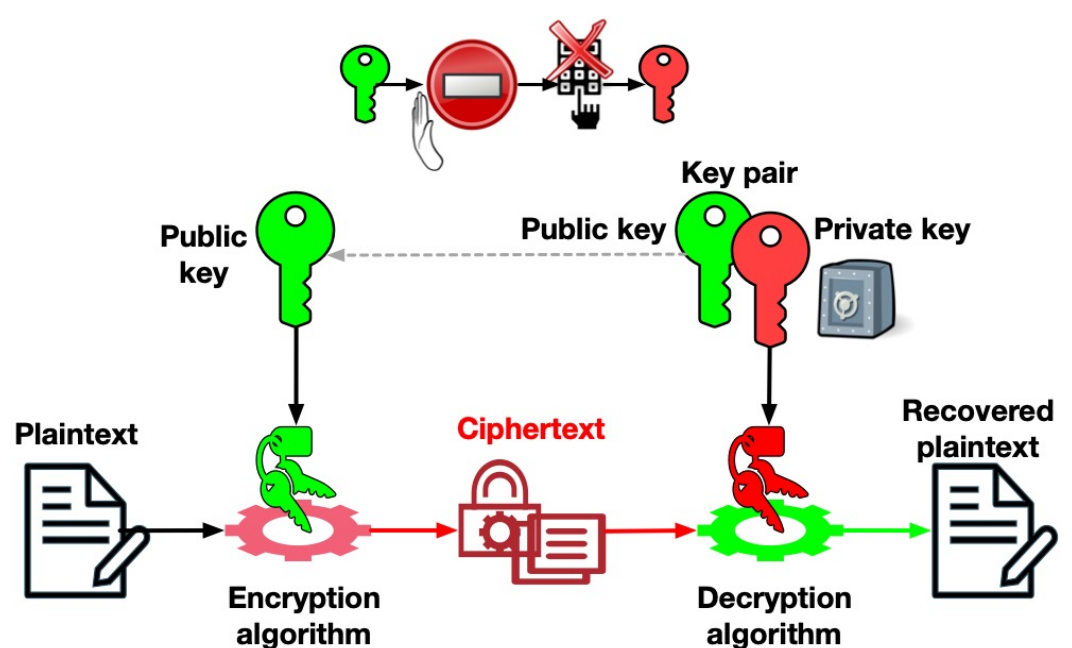

- We will create an algorithm with 2 separate keys:

- One (KE) will be used for encryption

- The other one (KD) will be used for decryption

- It should be infeasible to derive KD from KE

- May be possible in theory but must be VERY computationally-hard

- Encryption will apply KE, which can be non-secret (AKA “public key”)

- The encryption should apply a one-way function, so it cannot be reversed by anyone with KE

- Decryption will apply KD, which should be secret (AKA “private key”)

7.3 Asymmetric Algorithms

- This concept was published in the beginning of the 70’s

- Some cryptographers tried to design such algorithms but failed

- A practical algorithm was invented some years later, known as RSA

- It is named after the 3 co-inventors:

- Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir & Leonard Adleman

7.4 Asymmetric Cryptography – How?

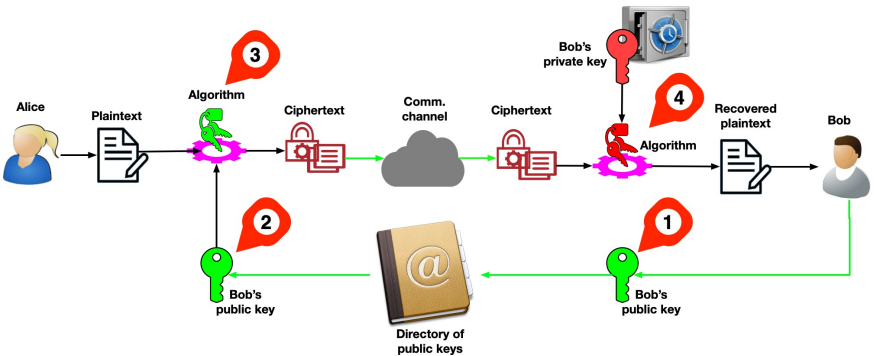

- Bob publishes his public key on a public, non-confidential directory

- Alice obtains Bob’s public key from this directory

- Alice encrypts her message with Bob’s public key

- Encryption is one-way, so cannot be reversed, even by Alice

- Bob applies his private key to decrypt the ciphertext and recover the plaintext

7.5 RSA Key Pair Generation

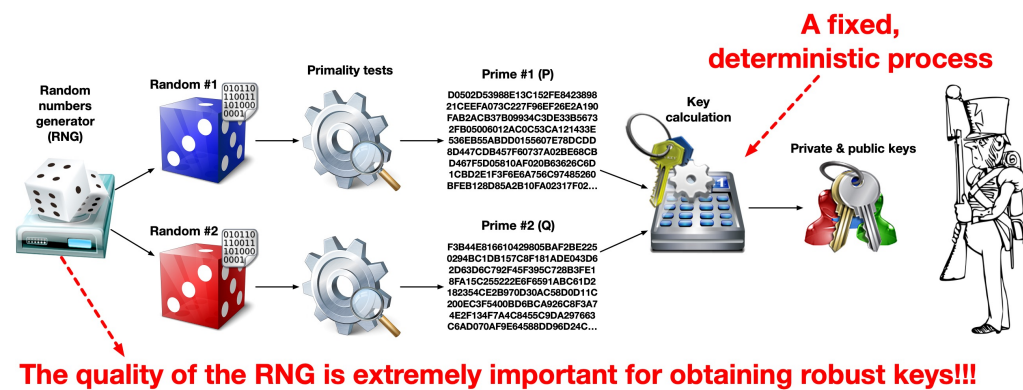

The a-symmetric RSA key pair is generated using the following method:

- 2 very big primes, P & Q (hundreds of digits each) are generated

- P & Q are then used to derive the RSA key pair (public key & private key)

- N = P X Q, the product of the two primes is calculated

- A prime number E is chosen with no common factor with (P - 1) X (Q - 1)

- usually, 65537 is used (=216 + 1)

- The number D is computed with the Extended Euclidean Algorithm (solving an equation for D)

- N & E is the public key, N & D is the private key

- P & Q are then securely erased (wiped) after key generation, keeping them is risky

7.6 RSA Key Pair Generation in Practice

- Practically, we don’t really know how to generate very large primes efficiently

- So, we just generate large random numbers and test them for primality

- We do enough tests to detect non-primes with high-enough assurance

- This process is rather slow, even on fast computers

7.7 The RSA Process

- Encryption: ciphertext = plaintextE MODULO N

- Decryption: plaintext = ciphertextD MODULO N

- Security depends on the difficulty of factoring very large numbers à a very hard task

- Brute-force attack: we can try every possible prime in range. More efficient attacks exist, but are still not practical on large enough keys (large enough = 3000 bits or more)

- Will take many billions of years and will consume too much energy, breaking one 2048-bits key is not practical with current technology

- Classical computing is not likely to help, quantum computing may become a big risk in the future (future =~ within a decade?)

- Break RSA 2048-bits key will require >4000 stable Qubits, state of the art is ~120 Qubits with questionable stability and too short stable lifespan, much less than is required

- A breakthrough in quantum computing may happen tomorrow or may not happen at all

Example

- Primes = 47 & 71

- N = 47 X 71 = 3337

- E = 79 (no common factors with 46 X 70 = 3220)

- D = 1019

- Plaintext = 688

- Encrypt: PLAINTEXTE MOD N = 68879 MOD 3337 = 1570

- Ciphertext: 1570

- Decrypt: CIPHERTEXTD MOD N = 15701019 MOD 3337 = 688

7.8 Alternative Algorithms

- RSA is the most common algorithm, but there are other alternatives

- The other alternatives are based on Elliptic Curves

- The elliptic curve is defined by the curve equation

- Not all elliptic curves are adequate

- The standards define curves that are robust for cryptography

- The private key is a randomly-chosen point on the curve

- Curve equation is used to find another point, which is the public key

- Easy to compute when the private point is known

- Very hard to compute when the private point is unknown

- Same security as RSA is achieved with much fewer bits

- But very easy to implement incorrectly!

8. Asymmetric Signatures

Digital Signatures

- Until now we had Alice & Bob, looking for confidentiality when they communicate with each other

- But when discussing security, we often look for all the CIA properties

- Not for the famous USA intelligence agency…

- CIA = Confidentiality, Integrity, Authenticity

- What about authenticity and integrity?

- Can we achieve them too?

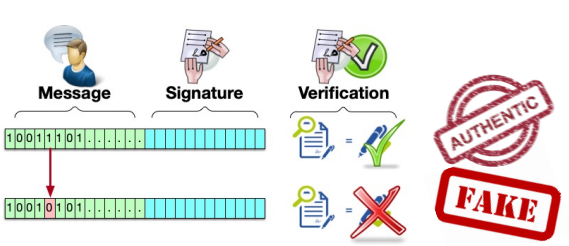

- A computation that only one specific person can perform is actually a “signature”

- A signature provides authenticity – we know who is the source of a signed message

- Others should be able to verify it - but not to sign

- This is where a-symmetric cryptography enters the stage again

- Encrypting with a PRIVATE key can be done only by the owner of that key

- Everyone else may decrypt with the PUBLIC key

- Correct decryption (i.e., recovering the original plaintext) is a strong proof that the owner of the PRIVATE key did the encryption, if the private key was not compromised

- This is the digital equivalent to signing

- The plaintext must be known to the verifiers, no confidentiality here

- We already know that a signature provides authenticity

- Remember the CIA paradigm?

- What about integrity?

- This is where a-symmetric cryptography enters the stage again

- Integrity is actually built-in

- Change one bit in the plaintext and the signature verification will fail